There are more than 3,900 confirmed planets beyond our solar system. Most of them have been detected because of their “transits” — instances when a planet crosses its star, momentarily blocking its light. These dips in starlight can tell astronomers a bit about a planet’s size and its distance from its star.

But knowing more about the planet, including whether it harbors oxygen, water, and other signs of life, requires far more powerful tools. Ideally, these would be much bigger telescopes in space, with light-gathering mirrors as wide as those of the largest ground observatories. NASA engineers are now developing designs for such next-generation space telescopes, including “segmented” telescopes with multiple small mirrors that could be assembled or unfurled to form one very large telescope once launched into space.

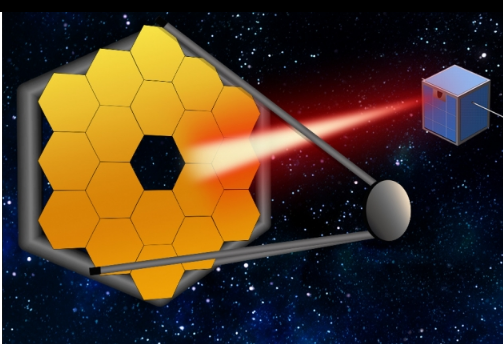

NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope is an example of a segmented primary mirror, with a diameter of 6.5 meters and 18 hexagonal segments. Next-generation space telescopes are expected to be as large as 15 meters, with over 100 mirror segments.

One challenge for segmented space telescopes is how to keep the mirror segments stable and pointing collectively toward an exoplanetary system. Such telescopes would be equipped with coronagraphs — instruments that are sensitive enough to discern between the light given off by a star and the considerably weaker light emitted by an orbiting planet. But the slightest shift in any of the telescope’s parts could throw off a coronagraph’s measurements and disrupt measurements of oxygen, water, or other planetary features.

Now MIT engineers propose that a second, shoebox-sized spacecraft equipped with a simple laser could fly at a distance from the large space telescope and act as a “guide star,” providing a steady, bright light near the target system that the telescope could use as a reference point in space to keep itself stable.

この情報へのアクセスはメンバーに限定されています。ログインしてください。メンバー登録は下記リンクをクリックしてください。